AN EXAMINATION OF THE PAIRED CATEGORIES OF PROPAGANDA IN THE LIGHT OF JACQUES ELLUL’S PROPAGANDA THEORY

Historical Background

The use of propaganda has been an integral

part of human history and we can trace its philosophical and theoretical

origins back to ancient Greece. Used effectively by Alexander the Great, the

Roman Empire, and the early Christians, propaganda became an integral part of

the religious conflicts of the Reformation (Ellul, 1967; Scribner, 1981;

Oettinger, 2001; McKinney, 2003; Martinson, 2001; Walton, 1997). In point of

fact, Martin Luther adopted the invention of the printing press in his fight

against the Catholic Church (Soergel, 1993; Wright, 2005; Watt, 1991; Bukofzer,

1960). The Catholic Church, in turn, not only used propaganda to propagate the

faith, but also to oppose Martin Luther. Both adversaries used songs as

instrument to spread their propagandas.

The opposition instinct in both camps made

propaganda to acquire pejorative connotations by losing its neutrality. As a

result, some words have been associated with propaganda; when they pop up in

discussions, what comes to mind is propaganda. They include lies, distortion,

deceit, manipulation, mind control, psychological warfare, brainwashing, and

palaver (Victoria O’Donnell &

Garth S. Jowett, 2012). The advent of printing technology, hence, provided the

ideal medium for the widespread use of propagandistic materials. Propagandists

quickly adopted each new medium of communication for use especially during the

American and French revolutions and later by Napoleon. By the end of the 19th

century, improvements in the size and speed of the mass media had greatly

increased the sophistication and effectiveness of propaganda (Moemeka, 1988;

Littlejohn, 1983; Hall, 1977; Marcuse, 1964).

This

study examines propaganda from the lens of Jacques Ellul evaluating his

perspectives on the categories of propaganda.

Objectives of the study

- To examine a brief history of Jacques

Ellul

- To evaluate the paired categories of

propaganda

- To evaluate other possible classification

bent not touched by Ellul

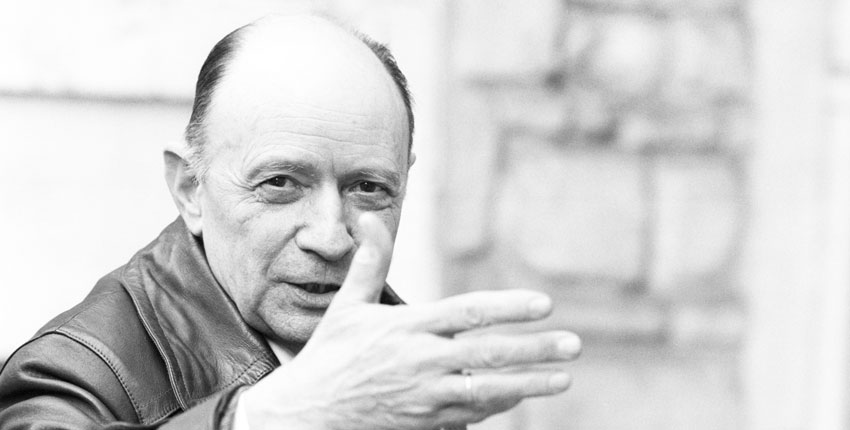

Who is Jacques Ellul? Brief historical

notes

Jacques Ellul is a French

Philosopher, Theologian, Legal Scholar, and Sociologist who became discharged

as a Professor from French universities by the Vichy regime in France. After

his discharge, Ellul became a leader in the French resistance during World War

II (Ellul, 1973). After the liberation of France, he became a professor at the University

of Bordeaux and wrote 58 books and numerous articles in his lifetime, the dominant

theme of which has been the threat to human freedom by modern technology. He

was the author of the book “Propaganda: The formation of men’s attitudes”. This

book first appeared in French in 1962, but later translated into English. The

book appears to be the first attempt to study propaganda from both sociological

and psychological approaches.

It presents a

sophisticated taxonomy for propaganda, including such paired opposites as political–sociological,

vertical–horizontal, rational–irrational, and agitation–integration. The book

contains Ellul's theories about the nature of propaganda to adapt the

individual to a society, to a living standard, and to an activity aiming to

make the individual serve and conform. Ellul's basic assumption in his theory

of propaganda differs from previous assumptions, which describe propaganda as a

manipulation for the purpose of changing ideas or opinions, or of making

individuals believe some ideas or facts, and finally of making them adhere to

some doctrine—all matters of the mind (Ellul, 1973). It tries to convince, to

bring about a decision, and to create a firm adherence to some truth.

Ellul views these

assumptions as a completely wrong line of thinking: to view propaganda as still

being what it was in 1850 is to cling to an obsolete concept of man and of the

means to influence him. It is to condemn oneself to understand nothing about propaganda

(Ellul, 1964; 1973; Castronovo, 2009). According to him, it

is essential that we understand propaganda in its modern form. Modern

propaganda is scientific and does not operate as it did in the 19th Century.

Modern propaganda is a systematic mode of communication within the world of

facts deployed to intentionally distort reality. According to Ellul (1973), the aim of modern propaganda

is no longer to modify ideas, but to provoke action. It is no longer to change

adherence to a doctrine, but to make the individual cling irrationally to a

process of action. It is no longer to transform an opinion, but to arouse an

active and mythical belief (Ellul, 1973).

Ellul believes modern propaganda is

intended to spark action towards a desired response by developing learned

attitudes, and that it draws from scientific analyses of psychology and sociology.

Ellul (1973) takes the view that prior attempts to define propaganda generally

left out the sociological angle. “Propaganda by its very

nature is an enterprise for perverting the significance of events and

insinuating false intentions. There are two salient aspects of this fact. First

of all, the propagandist must insist on the purity of his own intentions and,

at the same time, hurl accusations at his enemy. But the accusation is never

made haphazardly or groundlessly. The propagandist will not accuse the enemy of

just any misdeed; he will accuse him of the very intention that he himself has

and of trying to commit the very crime that he himself is about to commit (Ellul

in Jowett and O’Donnell, Propaganda and Persuasion, New and Classic Essays,

2006).”

Ellul

says, “Propaganda is necessarily false when it speaks of values, of truth, of

good, of justice, of happiness—and when it interprets and colors facts and

imputes meaning to them (Ellul, 1973; Brunello, 2014).” Ellul means that the

scientific application of modern propaganda is decidedly predatory. Written in

1967, Ellul’s criticism implies greater caution for the 21st Century.

For example, Ellul never could have considered the power of electronic social

networks like Facebook. Even so, the social network today provides a mode of

expanding propaganda cheaply, and with greater toxicity than the “chain emails”

of the last decade. Propagandists can now initiate politically motivated

disinformation campaigns very quickly.

What are his views concerning the

categories of propaganda

Although propaganda has many categories; however, it is almost

always in some form of activated ideology. Sometimes propaganda is agitative, attempting to rouse an

audience to certain ends and usually resulting in significant change; sometimes

it is integrative, attempting

to render an audience passive, accepting, and non-challenging (Szanto, 1978;

Evans, 1994). Propaganda is also described as white, gray, or black, in

relationship to an acknowledgment of its source and its accuracy of

information. However, Ellul

presents his views on the categories of propaganda according to the presumed

principle of relationship among them. He prefers to pair opposites together as

in the following format: political-sociological, vertical-horizontal,

rational-irrational, and agitation-integration. In this case, the reverse

knowledge of one provides the understanding of the other. We will examine the

categories briefly.

Political vs. Sociological Propaganda

Political Propaganda involves techniques

of influence employed by a government, a party, an administration, or a

pressure group with the intention of changing the behaviour of the public. The

themes and objectives of this type of propaganda are of a political nature. The

groups, government, party, administration or pressure group determine the goals

of political propaganda. The methods of political propaganda are calculated in

a precise manner and its main criteria is to disseminate an ideology for the

very purpose of making various political acts acceptable to the people (Ellul,

1973). There are two forms of political propaganda, tactical and strategic. Tactical

political propaganda seeks to obtain immediate results within a given framework

such as wartime pamphlets and loudspeakers to obtain immediate surrender of the

enemy.

Strategic political propaganda is not

concerned with speed, but rather it establishes the general line, the array of

arguments, and the staggering of campaigns. Political propaganda reversed is

sociological propaganda because the ideology penetrates by means of its sociological

context (Ellul, 1973). Propaganda, as it is traditionally known, implies an

attempt to spread an ideology through the mass media of communication in order

to lead the public to a desired action. In sociological propaganda even media

that are not controllable such as individual artwork, films, and writing,

reflect the ideology allowing for an accelerated penetration of the masses and

the individuals within them (Ellul, 1973). Sociological propaganda is a

phenomenon where a society seeks to integrate the maximum number of individuals

into itself.

Therefore, the group that operates

sociological propaganda unifies its members' behaviour according to a pattern,

then spreads its style of life abroad, and thus imposes itself on other groups.

Essentially sociological propaganda aims to increase conformity with the

environment that is of a collective nature by developing compliance with or

defense of the established order. It does this through long-term penetration

and progressive adaptation using all social currents. The propaganda element is

the way of life, which permeates the individual and then the individual begins

to express it in film, writing, or art without realising it. This involuntary

behaviour creates an expansion of society through advertising, the movies,

education, and magazines.

"The entire group, consciously or

not, expresses itself in this fashion; and to indicate, secondly that its

influence aims much more at an entire style of life (Ellul, 1973).” This type

of propaganda is not deliberate, but springs up spontaneously or unwittingly

within a culture or nation. This propaganda reinforces the individual's way of

life and represents this way of life as the best way. Sociological propaganda

creates an indisputable criterion for the individual to make judgments of good

and evil according to the order of the individual's way of life. Sociological

propaganda does not result in action; however, it can prepare the ground for direct

propaganda. From then on, the individual in the clutches of such sociological

propaganda believes that those who live this way are on the side of the angels,

and those who don't are bad (Ellul, 1973).

The propaganda of Christianity in the

middle ages is an example of this type of sociological propaganda. And in

present times certainly the most accomplished models of this type are American

and Chinese propaganda (Ellul, 1973). This sociological propaganda in the United States is a

natural result of the fundamental elements of American life. In the beginning,

the United States had to unify a disparate population that came from all the

countries of Europe and had diverse traditions and tendencies. A way of rapid

assimilation had to be found: that was the great political problem of the

United States at the end of the nineteenth century. The solution was

psychological standardisation—that is, simply to use a way of life as the basis

of unification and as an instrument of propaganda.

Vertical vs. Horizontal Propaganda

Vertical propaganda is similar to direct

propaganda that aims at the individual in the mass and is renewed constantly. Agitators

use this propaganda to accomplish their desired goals. One trait of vertical propaganda is that the

propagandee remains alone even though he is part of a crowd. His shouts of

enthusiasm or hatred, though part of the shouts of the crowd, do not put him in

communication with others. His shouts are only a response to the leader. This

kind of propaganda requires a passive attitude from those subjected to it. They

are seized; they are manipulated; they are committed; they experience wbat they

are asked to experience (Ellul, 1973). In fact, they are really transformed

into objects. Consider, for instance, the quasi-hypnotic condition of those

propagandised at a meeting.

There, the individual is depersonalised.

His decisions are no longer his own, but those suggested by the leader, imposed

by a conditioned reflex. When we say that this is a passive attitude, we do not

mean that the propagandee does not act. On the contrary, he acts with vigor and

passion, but his action is not his own, though he believes it is. Throughout, his

action is conceived and willed outside of him; the propagandist is acting

through him, reducing him to the condition of a passive instrument. He is

mechanised, dominated, hence passive. This is all the more so because he often

is plunged into a mass of propagandees in which he loses his individuality and

becomes one element among others, inseparable from the crowd and inconceivable

without it.

In any case, vertical

propaganda is by far the most widespread —whether Hitler's or Stalin's, that of

the French government since 1950, or that of the United

States. It is in one sense the easiest to make, but its direct effects are

extremely perishable, and it must be renewed constantly as we said earlier. Horizontal propaganda is a much more recent development. We

know it in two forms: Chinese propaganda and group dynamics in human relations.

The first is political propaganda; the second is sociological propaganda; both are integration

propaganda (Ellul, 1973).

This propaganda can be

called horizontal because it is made inside the group (not from the

top), where, in principle, all

individuals are equal and there is no leader. The individual makes contact with

others at his own level rather than with a leader. Such propaganda therefore

always seeks "conscious adherence.”

Its content is presented

in didactic fashion and addressed to the intelligence. The leader, the

propagandist, is there only as a sort of animator

or discussion leader. Sometimes his presence and his identity

are not even known—for example, the "ghost

writer" in certain American groups, or the "police spy" in Chinese

groups. The individual's adherence to his group is "conscious" because

he is aware of it and recognises it, but it is ultimately involuntary because

he is trapped in dialectic and in a group that leads him unfailingly to this

adherence. His adherence is also "intellectual" because he can

express his conviction clearly and logically, but it is not genuine because the

information, the data, the reasoning that have led him to adhere to the group

were themselves deliberately falsified in order to lead him there.

But the most remarkable

characteristic of horizontal propaganda is the small group. The individual participates

actively in the life of this group in a genuine and lively dialogue. In China

the group is watched carefully to see that each member speaks, expresses

himself, gives his opinions. Only in speaking will the individual gradually

discover his own convictions (which also will be those of the group), become

irrevocably involved, and help others to form their opinions (which are

identical). Each individual helps to form the opinion of the group, but the

group helps each individual to discover the correct line. For, miraculously, it

is always the correct line, the anticipated solution, the "proper"

convictions, which are eventually discovered. All the participants are placed

on an equal footing, meetings are intimate, discussion is informal,

and no leader presides.

Progress is slow; there

must be many meetings each

recalling events of the preceding

one so that participants can share a common experience. To produce

"voluntary" rather than mechanical adherence, and to create a

solution that is "found" by the individual rather than imposed from

above is indeed a very

advanced method, much more effective and binding than the mechanical action of

vertical propaganda. When the individual is mechanised, he can be manipulated

easily. But to put the individual in a position where he apparently has a

freedom of choice and still obtains from him what one expects, is much more

subtle and risky.

Vertical propaganda needs the huge apparatus of the mass media of communication; horizontal propaganda

needs a huge organisation of people. Each individual must be inserted into a

group, if possible into several groups with convergent actions. The group must

be homogeneous, specialised and small: fifteen to twenty is the optimum figure to permit

active participation by each person. This group must comprise individuals of

the same sex, class, age, and environment. Most friction between individuals

can then be ironed out and all factors eliminated, which might distract

attention, splinter motivations, and prevent the establishment of the proper

line. Therefore, a great many groups are

needed (there are millions in China), as well as a great many group leaders.

That is the principal problem.

Mao believes each member

of a group must be a propagandist for all. However, this form of propaganda needs

two conditions. First is lack of contact between groups. A member of a small

group must not belong to other groups in which he would be subjected to other

influence that would give him a chance to find himself again and with it, the strength to resist.

This is why the Chinese Communists insisted on breaking up traditional groups, such

as the family, which is a private and heterogeneous group (with different ages,

sexes, and occupations). The family is a

tremendous obstacle to such propaganda. In China, where the family was still

very powerful, it had to be broken up. The problem is very different in the

United States and in the Western societies; there the social structures are

sufficiently flexible and disintegrated to be no obstacle. However, in horizontal propaganda there is no top down

structure like we have in vertical propaganda. Schools are a primary mechanism

for integrating the individual into the way of life.

Rational vs. Irrational Propaganda

Propaganda is addressed to the individual

on the foundation of feelings and passions, which are irrational; however, the

content of propaganda does address reason and experience when it presents

information and furnishes facts making it rational as well. It is important for

propaganda to be rational because modern man needs relation to facts. Modern

man wants to be convinced that by acting in a certain way, he is obeying reason

in order to have self-justification.

According to Ellul (1973) describing the

effect of the film, Algérié Fran‚caíse

and the nature of American bulletins, “Similarly, the propaganda of French grandeur since 1956 is a rational and factual propaganda; French films in

particular are almost all centered around French technological successes. The film

Algérié

Fran‚caíse is

an economic film, overloaded with economic geography and statistics (Ellul,

1973). But it is still propaganda. Such rational propaganda is practiced by

various regimes. … American propaganda, out of concern for honesty and

democratic conviction, also attempts to be rational and factual. The news

bulletins of the American services are a typical example of rational propaganda

based on "knowledge" and information.” We can say that the more

progress we make, the more propaganda becomes rational and the more it is based on serious

arguments, on dissemination of knowledge, on factual information, figures, and

statistics.'

Purely impassioned and emotional

propaganda is disappearing. Even such propaganda contained elements of fact:

Hitler’s most inflammatory speeches always contained some facts, which served

as base or pretext. It is unusual nowadays to find a frenzied propaganda

composed solely of claims without relation to reality. However, the overarching problem in this modern time

lies in the effect of propaganda, which, most times, is irrational. The

challenge is creating an irrational response on the basis of rational and

factual elements by leaving an impression on an individual that remains long after

the facts have faded away. No framework exists to compel individuals to act

based rather on facts than emotional pressure, the vision of the future, or the

myth.

Agitation vs. Integration Propaganda

May be we go the Lenin way by giving the

difference between agitation and propaganda. According to Oxford dictionary, to

agitate is "to excite or stir it up," whereas

propaganda is a "systematic scheme or concerted movement, for the

propagation of some creed or doctrine." These

definitions are not a bad starting point. Agitation focuses on an immediate

issue, seeking to 'stir up' action around that issue. Propaganda is concerned

with the more systematic exposition of ideas. The

pioneer Russian Marxist Plekhanov pointed out an important consequence of this

distinction. "A propagandist presents many ideas to one or a few persons;

an agitator presents only one or a few ideas, but presents them to a mass of people

(Duncan, 1984)." Like all such generalisations, this one should not be

taken too literally.

Propaganda can, in favourable circumstances, reach

thousands and tens of thousands. And the 'mass of people' reached by agitation

is a highly variable quantity. Nevertheless, the general point is sound. Now

back to Lenin! Lenin, in his book, What Is to Be Done,

develops this idea: The propagandist, dealing with, say, the question

of unemployment, must explain the capitalistic nature of crises, the cause of

their inevitability in modern society, the necessity for the transformation of

this society into a socialist society, etc (Duncan, 1984). In a word, he must

present "many ideas", so many indeed, that they will be understood as

an integral whole by a (comparatively) few persons. The agitator, however,

speaking on the same subject, will take as an illustration the death of an

unemployed worker's family from starvation, the growing impoverishment etc

(Duncan, 1984).

Utilising this fact known to all, however, the

agitator directs his efforts to presenting a single idea to the

"masses." Consequently the propagandist operates chiefly by means of

the printed word; the agitator by means of the spoken word. On this last point

Lenin was wrong because he was too one-sided. As he himself had argued, before

and after he wrote the statement above, the revolutionary paper can and must be

a most effective agitator. But this is a secondary matter. The important thing

is that agitation, spoken or written, does not explain everything. Propaganda of agitation seeks to mobilise

people in order to destroy the established order and/or government. It seeks

rebellion by provoking a crisis or unleashing explosive movements during one.

It momentarily subverts the habits,

customs, and beliefs that were obstacles to making great leap forward by

addressing the internal elements in each of us. It eradicates the individual

out of his normal framework and then proceeds to plunge him into enthusiasm. It

then suggests extraordinary goals, which nevertheless seem to the propagandee

completely within reach. However, this enthusiasm last only a short time so the

objective must be achieved quickly and then a period of rest follows. People

cannot be kept in a "state of perpetual enthusiasm and insecurity (Ellul,

1973)". Propagandist who knows that hate is one of the most profitable

resources when drawn out of an individual is the one that incites rebellion.

Agitation propaganda is usually thought of

as propaganda in that it aims to influence people to act. However, we should

affirm here that government too can initiate agitation propaganda against a

segment of society seen as obstacle to making great leap forward. Integration

propaganda, on the other hand, is a more subtle form that aims to reinforce

cultural norms. This is sociological in nature because it provides stability to

society by supporting the "way of life" and the myths within a

culture (Ellul, 1973). It is propaganda of conformity that requires

participation in the social body. This type of propaganda is more prominent and

permanent, yet it is not as recognised as agitation propaganda. Basically,

agitation propaganda provides the motive force when needed and when not needed

integration propaganda provides the context and backdrop.

Though not exclusive, however, integration

propaganda provides the most preferred instrument of government. This is

because of its stabilizing and unifying influence in social life. In the United

States, integration propaganda is much more subtle and complex than agitation

propaganda (Ellul, 1973). It seeks not temporary excitement, but total moulding

of the person in depth. Here, propagandists utilise both mass media of

communication and psychological and opinion analysis. It is the most important

political and sociological instrument in a world divided by subversive

influences of agitation propaganda. The more comfortable, cultivated and

informed the milieu to which it is addressed, the better it works.

Other Classification Bent

White vs. Black vs. Gray Propaganda

Jacques Ellul did not examine these types

of propaganda in his analysis. This is one criticism that one can say limits

his overall evaluation, but there is need to present some distinctions in

respect of these propaganda types. While there are discrepancies in

the way people define these terms, Garth S. Jowett and Victoria O’Donnell

(2012) use the following labels:

White propaganda comes from a source that is

identified correctly, and the information in the message tends to be accurate. Although

what listeners hear is reasonably close to the truth, it is presented in a

manner that attempts to convince the audience that the sender is the ‘good guy’

with the best ideas and political ideology (Victoria O’Donnell & Garth S.

Jowett, 2012 on Battle of the Midway). White propaganda is used to boost

national celebrations and regional chauvinism with overt patriotism. This

is what one hears on Radio Moscow and VOA during peacetime. For instance, the

2008 Summer Olympics in Beijing, China, had all the usual nations represented,

but in addition to the events themselves, American television primarily focused

on biographical profiles of American athletes, especially champion swimmer

Michael Phelps.

Black propaganda, on the other hand, is credited to a false source, and

it spreads lies, fabrications, and deceptions. Black

propaganda includes all types of creative deceit, and this type of propaganda

gets the most attention when it is revealed. The success or failure of black

propaganda depends on the receiver’s willingness to accept the credibility of

the source and the content of the message. Care has to be taken to place the

sources and messages within a social, cultural, and political framework of the

target audience. If the sender misunderstands the audience and therefore

designs a message that does not fit, black propaganda may appear suspicious and

tends to fail. However, disinformation is another term used to describe black propaganda. Disinformation is usually

considered black propaganda because it is covert and uses false information.

In fact, the

word disinformation is a

cognate for the Russian dezinformatsia,

taken from the name of a division of the KGB devoted to black propaganda.

Disinformation means, “False, incomplete, or misleading information that is

passed, fed, or confirmed to a targeted individual, group, or country (Shultz

& Godson, 1984).” It is not misinformation that is merely misguided or

erroneous information. Disinformation is made up of news stories deliberately

designed to weaken adversaries and planted in newspapers by journalists who are

actually secret agents of a foreign country. The stories are passed off as real

and from credible source. Ladislav Bittmann, former deputy chief of the

Disinformation Department of the Czechoslovak Intelligence Service, in

testimony before the House Committee on Intelligence of the U.S. Congress in

February 1980, said,

If somebody had at this moment the

magic key that would open the Soviet bloc intelligence safes and looked into

the files of secret agents operating in Western countries, he would be

surprised. A relatively high percentage of secret agents are journalists. …

There are newspapers around the world penetrated by the Communist Intelligence

services. (Brownfield, 1984, p. 6)

A popular black propaganda credited America as the

developer of the virus responsible for acquired immune

deficiency syndrome (AIDS) for biological warfare. The story appeared in the

news media of more than 60 countries, including Zimbabwe, while the nonaligned

countries were having a conference there (Victoria O’Donnell & Garth S. Jowett, 2012). The story

also appeared in the October 26, 1986, issue of London’s Sunday Express after Express reporters interviewed two

people from East Berlin who repeated the story. Subtle variations continued to

appear in the world press, including an East German broadcast of the story into

Turkey that suggested it might be wise to get rid of U.S. bases because of

servicemen infected with AIDS. Interestingly, it has been the desire of the

Soviet Union to plant such stories in foreign newspapers to discredit the

United States. Increasing evidence shows that major world powers practise

disinformation, which reflects the reality of international politics.

In the same vein, gray

propaganda is somewhere between white and black propaganda. Here, the

source may or may not be correctly identified, and the accuracy of information

is uncertain. Gray propaganda is used to embarrass an

enemy or competitor. Radio Moscow took advantage of the assassinations of

Martin Luther King Jr. and John F. Kennedy to derogate the United States. VOA

did not miss the opportunity to offer similar commentaries about Russia’s

invasion of Afghanistan or the arrests of Jewish dissidents. This propaganda

involves planting of favourable stories in foreign newspapers. This practice

has long standing root in the United States. The United States plants

favourable stories about itself in foreign newspapers as the source. The

practice has been sanctioned by the U.S. Department of Defense.

An unclassified

summary of the policy confirmed this as released by the Associated Press:

“Psychological operations are a central part of information operations and

contribute to achieving the commander’s objectives. They are aimed at conveying

selected, truthful information to foreign audiences to influence their

emotions, reasoning, and ultimately the behavior of governments and other

entities (Pentagon Propaganda Program within the Law, 2006).” It is not only

governments that practise planting favourable stories, for private organisations

do it as well. Since 1980s, the use of video news releases (VNRs) inserted in

television news programmes has been on the increase (Pavlik, 2006). However, while

these definitions are in themselves fairly ambiguous, one could argue that all

forms of persuasion fall into the category of white propaganda at the very

least, extending the general definition of propaganda to anything that argues

an opinion.

Other Criteria

for Classification

Propaganda may be classified

upon the basis of many possible criteria. Some are carried on by organisations

like the Anti-Cigarette League, which have a definite and restricted objective.

Others are conducted by organisations, like most civic associations, which have

a rather general and diffused purpose (Harold Lasswell, 1927). According to

Lasswell (1927), this objective may be revolutionary or counter-revolutionary,

reformist or counter-reformist, depending upon whether or not a sweeping

institutional change is involved. Propaganda may be carried on by

organisations, which rely almost exclusively upon it or which use it as an

auxiliary implement among several means of social control. Some propagandas are

essentially temporary while some others are comparatively permanent. Some

propagandas are intra-group, in the sense that they exist to consolidate an

existing attitude and not, like the extra-group propagandas, to assume the

additional burden of proselytising (Harold Lasswell, 1927).

Those who hope to reap

direct, tangible, and substantial gains man some propaganda. Those who are

content with a remote, intangible, and rather imprecise advantage staff other

propagandas. Men who make running propaganda their life work run some

propagandas, and amateurs handle others. Some depend upon a central or skeleton

staff and others rely upon widespread and catholic associations. One propaganda

group may flourish in secret like Biafra radio, and another may invite

publicity like Boko Haram. Besides all these conceivable and often valuable

distinctions, propagandas may be conveniently divided according to the object

toward which it is proposed to modify or crystallise an attitude.

According to Lasswell (1927), some propagandas exist to organise an attitude toward a person, like Mr. Coolidge or Mr. Smith. Others exist to organise an attitude toward a group, like the Japanese or the workers. Others exist to organise an attitude toward a policy or institution, like free trade or parliamentary government. Still others exist to organise an attitude toward a mode of personal participation, like buying war bonds or joining the marines (Harold Lasswell, 1927). No propaganda fits tightly into its category of major emphasis, and we must remember that people invent pigeonholes to serve convenience and not to satisfy yearnings for the immortal and the immutable. Lasswell maintains that the problem of the propagandist is to intensify the attitudes favourable to his purpose, to reverse the attitudes hostile to it, and to attract the indifferent, or, at the worst, to prevent them from assuming a hostile bent.

If you need the full paper, you can contact me by dropping a comment.

Write your comment